The Importance of Your Data

While we have all been conditioned to view an animal and make assumptions on their longevity, muscling, and growth performance, in reality, without documenting the animal’s actual phenotypes (anything that can be measured) we can’t make logical predictions on how the animal will influence their progeny and your herd as a whole.

Take time to give a close look over this section as we present to you the foundation of effective performance measuring.

The Importance of Your Data

- IGS Multi-breed Genetic Evaluation

- The Keystone of Your Data

- Start Recording Your Herd

- What You Can Do for Your National Cattle Evaluation

Getting the Most From the IGS Multi-breed Genetic Evaluation

By Drs. Jackie Atkins, Matt Spangler, Bob Weaber, and Wade Shafer

Best Practices for Seedstock Producers

Clearly defined breeding objectives — With the ability to increase the rate of genetic change comes the possibility to make mistakes at a faster pace. Breeding goals need to be clearly identified to ensure selection at the nucleus level matches the needs (profit-oriented) of the commercial industry.

Whole herd reporting — Inventory-based reporting captures more complete phenotypes on reproduction and longevity traits and thus creates more accurate genetic selection tools.

Proper contemporary groups — It is important for the precision of the genetic evaluation to group animals treated uniformly. Proper reporting of contemporary groups reduces bias in EPD.

Take data collection and reporting seriously. — Phenotypes are the fuel that drives the genetic evaluation. Take pride in collecting accurate data. If possible, collect additional phenotypes like mature cow weight, cow body condition score, udder scores, feed intake, and carcass data.

Phenotypic data collection for economically relevant traits needs to improve in both quantity and quality. — The quantity and quality of fertility traits need to dramatically improve. Providing disposal codes to identify why females leave the herd is vital. Commercial data resources, where the true economically relevant traits exist, are going to become more critical to capture.

Use index-based selection. — As the list of published EPD continues to grow, using economic selection indices will become even more helpful to reduce the complexity of multiple trait selection. If the number of EPD increase, tools to reduce the complexity of sire selection for commercial producers must continue to develop. Breed associations and seedstock producers have the obligation to aid commercial clientele in making profitable bull selection decisions.

Use genomics — Genomic selection offers an opportunity to increase the rate of genetic change and break the antagonistic relationship between generation interval (the average age of the parents when the next generation is born) and the accuracy of selection (e.g., the accuracy of EPD) — two components that determine the rate of genetic change. However, as with any tool, genomic information

must be used correctly and to its fullest extent. What is proposed herein is a list of ‘best practices’ for producers and breed organizations relative to genomic testing.

Best Practices for Genomic Testing:

1.) All animals within a contemporary group should be genotyped. If genomic data are meant to truly enable selection decisions, this information must be collected on animals before selection decisions are made. The return on investment of this technology is substantially reduced if it is used after the decision is made.

2.) Both male and female animals should be genotyped. The promise of genomic selection has always suggested that the largest impact will be for traits that are lowly heritable and/or sex-limited (e.g., fertility) or those that are not routinely collected (e.g., disease). This is indeed true, but it necessitates that genotyped animals have phenotypes. For sex-limited traits, this becomes a critical choke point given the vast majority of genotyped cattle are males. If producers wish to have genomic-enhanced EPD for traits such as calving ease maternal and heifer pregnancy, they must begin or continue to genotype females. The ASA has a unique program called the Cow Herd DNA Roundup (CHR) to help herds collect female genotypes (see pop-out box for more information).

3.) Genotypes can provide useful information in addition to predictions of additive genetic merit. Do not forget the value in correcting parentage errors, tracking inbreeding levels, identifying unfavorable haplotypes, estimating breed composition, and estimating retained heterozygosity. All of these can be garnered from populations that have a well-defined set of genotyping protocols.

The beef industry should be congratulated for the rapid adoption of genomic technology, but there is a lot of work to do. Of critical importance is the fact that genomic technology will continue to change and does not replace the need for phenotypes nor the fundamental understanding of traditional selection principles including EPD and accuracy.

The Keystone of Your Data

Contemporary Grouping

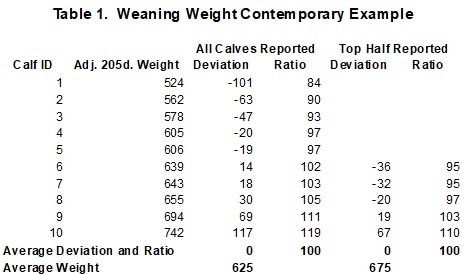

The purpose of a contemporary group is to identify measurable differences in animals raised under the same management and environmental conditions. By minimizing variations in management and environment as much as possible, it is easier to identify differences in weights or other measurements due to genetics. There are other non-genetic differences in weights such as the age of the animal and its dam when the measurement was taken. These differences are accounted for by adjusting the actual weights or measurements to a common base. For example, actual weaning weight is adjusted to a 205-day adjusted weight. An adjusted weight by itself provides no genetic information. Genetic information is only obtained when an adjusted weight is properly compared to adjusted weights of other animals that had the same opportunity to perform, i.e. in the same contemporary group.

Since contemporary groups are an important part of genetic evaluation, having the best information to form contemporary groups is important. Errors are introduced when animals are treated differently or raised in different environments but put in the same contemporary group.

Breeders submit weights and scores on animals and these measurements are adjusted for such things as the animal’s age and the age of its dam. But it’s the contemporary group that adds meaning to those measurements. It answers the question, “Compared to what?”.

Start Recording Your Herd

You now understand the importance of contemporary groups, the rules behind them and what ratios mean. Next, it is time for you to start recording your cattle to best analyze them for future breeding objectives. The ASA has very important guidelines that one must follow in order to properly record your animals.

Below are listed the criteria ASA uses to form contemporary groups. There are fixed criteria such as sex and weaning weight date, and also criteria that breeders set to help form proper contemporary groups such as herd ID, management code and pasture unit for weaning, feeding unit for yearling and scan group for ultrasound. All criteria are used to form contemporary groups. For example, animals with different weaning weight dates will not be weaning contemporaries even if they have the same management code and pasture unit. Likewise, animals will not be weaning contemporaries if they have different management codes or pasture units even if they have the same weaning weight dates.

American Simmental Association criteria for forming contemporary groups:

At Birth animals must

- Be weighed

- Have the same initial owner account

- Be reported at the same time, for interim EPD

- Have the same herd ID

- Have the same sex; females or males, steers are male at birth

- Be a single birth

- Be born in the same calving season (Jan to Jun or Jul to Dec)

At Weaning animals must

- Be in the same birth contemporary group

- Have the same weaning weight date

- Have the same management code

- Have the same pasture unit

- Be in the same age range at weaning (between 160-250 days)

At Yearling animals must

- Be in the same weaning contemporary group

- Have the same yearling weight date

- Have the same feeding unit

- Have the same yearling sex (to handle bulls steered after weaning)

- Be in the same age range at yearling (between 330-440 days)

- There must be at least 60 days between weaning and yearling weight dates

For Ultrasound animals must

- Be in the same weaning contemporary group

- Have the same scan date

- Have the same scan group designation

- Be the same sex when scanned (bulls are separated from steers)

- Be in the same age range when scanned (between 330-440 days)

You can hire a certified Ultrasound technician by searching http://ultrasoundbeef.com/Technicians.php