Performance Data Reporting

- Adjusted Weights

- Calving Records

- Carcass

- Contemporary Groups

- Docility

- Growth Traits

- Feet and Legs

- Feed Intake

- Mature Cow

- Performance Data Collection Guide

- Pulmonary Arterial Pressure

- Ratios

- Stayability

Adjusted Weights

Known environmental factors can influence the weight of a calf at different ages. Standardizing weights to remove influences that aren’t heritable is important for genetic comparisons. To make comparisons, breeders should only use adjusted weights among animals in a contemporary group. Making comparisons with non-adjusted values or across contemporary groups is inappropriate. The best tool for selecting genetics for a trait is an EPD (when available) or ideally using an index designed to meet your operation objectives. Adjusted values should not be used to make selection decisions when EPD are available.

Adjusted Birth Weight:

Birth weights are adjusted based on sex of the calf, age of the dam, breed of the dam, and direct heterosis. Reported weights must be between 30 and 160 pounds.

Adjusted Weaning Weight:

Weaning weights are adjusted to a standard age and adjusted based on sex of the calf, breed of the dam, age of the dam, and direct and maternal heterosis. Reported weights must be between 200 and 1200 pounds, and between 100 and 310 days of age.

Adjusted Yearling Weight:

From the weaning weight, yearling weight is adjusted to 160 days with additional adjustment made for direct heterosis. Reported weights must be between 350 and 2,000 pounds, and between 270 and 500 days of age.

It is important to note that the ASA genetic evaluation accounts for breed and heterosis differences that may produce differences in adjusted values if you were to use the BIF adjustment equations.

Calving Records

Calving data is incredibly useful and economically important. Particularly in the case of measuring calving difficulty, improving the genetic merit of seedstock animals for the number of live calves born is vital to the beef industry. Calving Ease, both direct and maternal, helps improve selection for calves being born unassisted. At the same time, breeders should also be collecting Birth Weight and Teat/Udder scores.

Calving Ease Score indicates how easily a calf was born. Only scores 1 through 4 are used in the genetic evaluation of calving ease, but scores 5 through 7 can be used to further describe the calving event. If a calf's birth was unobserved (hence unassisted), use a 1 as the primary score. If entering scores into ASA’s Herdbook, every calf should have a primary score (1–4) but two-digit numbers may be used for more thorough accounting of calving. Examples: Use 36 to indicate a hard pull and dead on arrival. Use a 25 to indicate an easy pull with an abnormal presentation.

1 = Born unassisted

2 = Easy pull

3 = Hard pull

4 = Cesarean

5 = Abnormal presentation (omitted from genetic evaluation)

6 = Dead on arrival (omitted from genetic evaluation)

7 = Premature (omitted from genetic evaluation)

Birth weight records should be collected on calves within 24 hours after birth. Hoof tapes are an acceptable method to measure birth weight, but please indicate when a tape is used and use the same method for the entire calving season.

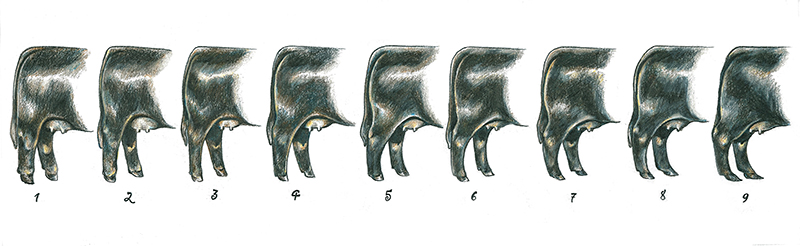

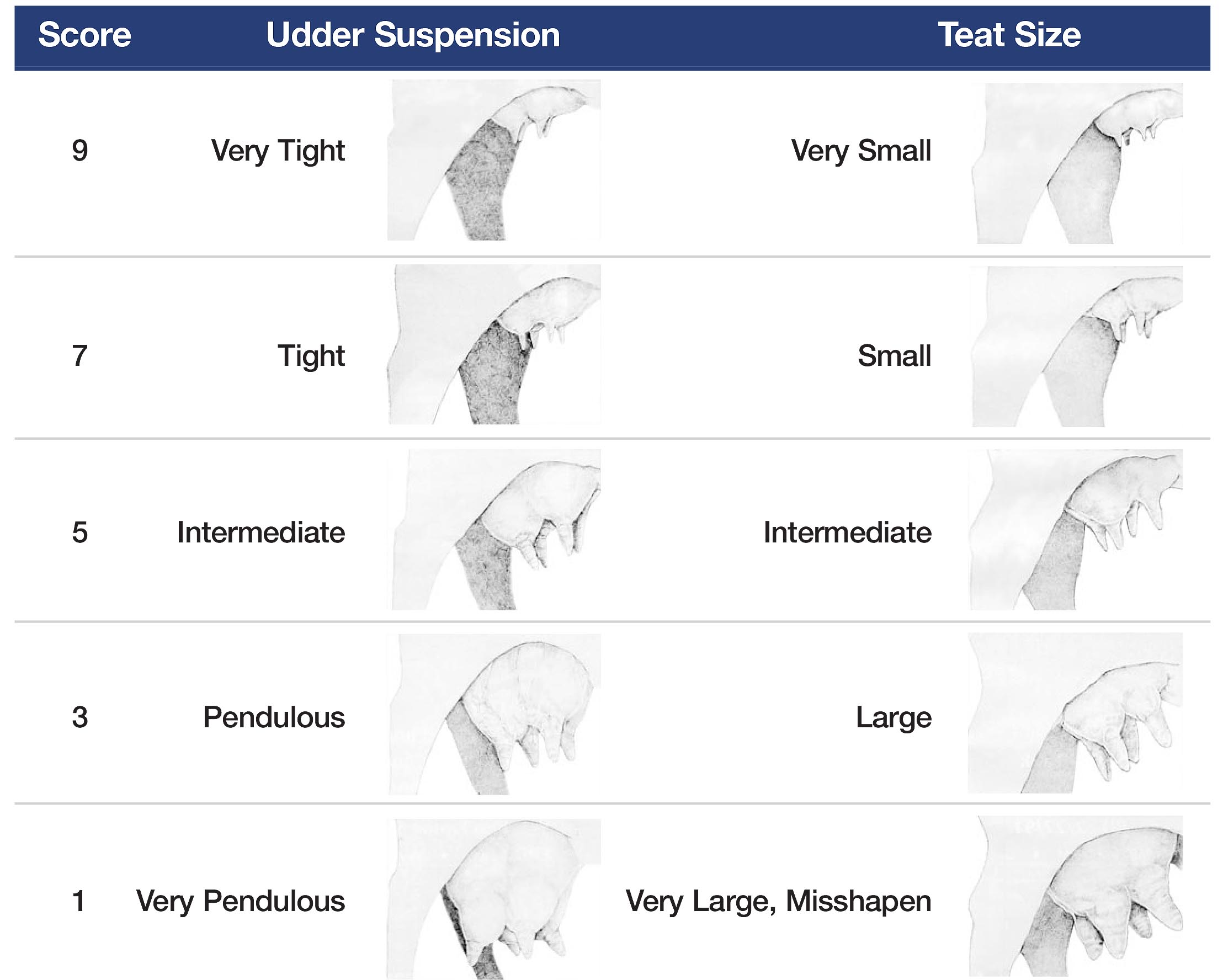

Udder and Teat Scores should be collected within 24 hours of calving. Two scores are assigned based on udder suspension (1–9; with 1 being very pendulous and 9 being very tight) and teat size (1–9 with 9 being very small and 1 being large and misshapen). Ideally one person scores all the udders/teats during the calving season for consistency.

Carcass

Terminal carcass data is important in developing an understanding of end-product merit and terminal performance for the progeny of seedstock animals. Consumer demand for high-quality, nutritious, and affordable beef has increased, and so, too, has the demand to make genetic improvements in those characteristics. Commercial cattlemen who are actively marketing their animals on grid-based channels need to identify bulls that will perform well for yield and quality marketing. Genetic predictions for terminal traits such as USDA Yield Grade, carcass weight, marbling, ribeye area, and backfat thickness all benefit the improved selection of terminal traits. These trait predictions rely heavily on harvest plant terminal data.

Carcass Data:

Historically, less than 2% of animal counts in ASA’s database annually will be harvested and carcass data returned to the ASA. Programs like the Carcass Merit Program (CMP) and Carcass Expansion Program (CXP) have garnered terminal data to fuel carcass evaluations. If you plan to retain ownership on subsets of your calves or enroll cooperator herds, you can find a list of the required information for carcass evaluation below.

Data Submission Requirements:

All data must be submitted in the original electronic spreadsheet document obtained from the packing plant or feedlot personnel. These data are then sent via email to carcdata@simmgene.com, where an ASA staff member will upload results to the corresponding registration numbers. In order for carcass data to be accepted, animals must first be on file with the ASA, and birth through weaning data turned in.

Minimum Data Requirements in order for data to be processed:

Animal Identification (Calf ID/Tattoo) - must correspond to an ASA number.

- Harvest Date - Animals must be between 270 and 900 days of age.

- Harvest Plant

- Carcass Weight

- Marbling Score

- Ribeye Area (inches squared)

- Backfat thickness

Carcass Ultrasound:

The collection of terminal data can be incredibly difficult due to long wait times from birth until harvest, and few seedstock breeders actively retaining ownership. To fill this void, carcass ultrasound can be an appropriate substitute when few actual carcass data are available.

Carcass Ultrasound scan data must be submitted by an accredited Ultrasound Guidelines Committee (UGC) technician. Scans will be accepted on bulls and heifers between 270 and 500 days of age. Scans on % IMF, Fat Thickness, and Ribeye Area are submitted to the ASA, where those will be included in the carcass genetic evaluation as correlated traits.

Data Submission Requirements:

Prior to scanning, your technician will require an ASA-generated list (barnsheet) of the animals you plan to process. Barnsheets can be obtained by logging on to your Herdbook account and clicking on the barnsheet icon (under the My Herd category). Several options are then available to sort the animals you plan to have scanned onto your barnsheet. When the appropriate animals to be scanned are stored, you can print a copy of the barnsheet for yourself as well as electronically submit a copy to the processing lab of your choice. Animals must be on file with the ASA to appear on your barnsheet.

For Ultrasound Data to process accurately, the following needs to be considered:

- ASA must have weaning data on file in order to get adjusted ultrasound calculations.

- Animals have to be contemporaries at weaning in order to be contemporaries at ultrasound.

- Animals outside of the age range (270–500 days) for ultrasound will not get ultrasound adjustments.

- A twin will be grouped by itself at ultrasound, same as other traits.

Contemporary Groups

Perhaps the most important aspect of proper genetic evaluation is the reporting of true and accurate contemporary groups. An animal’s environment can not be inherited from parent to progeny. So understanding the influence of management, nutrition, and environmental influences on an animal’s own performance is important to making accurate selection decisions. Contemporary grouping is the mechanism by which our statistical models can differentiate genetic potential from environmental influences in a phenotype.

The way this is done is by assuming all animals in a contemporary group have an equivalent environment and that differences in performance are due to genetics. If a subset of calves that perform above the rest of the group are all sired by the same sire, then we can postulate that a particular sire’s genetics are superior to other sires’ genetics represented in the contemporary group.

Example of contemporary groups:

Birth CG: Breeder / Herd / Year Born / Season / Sex / Management Code

Weaning Weight CG: Breeder / Herd / Year Born / Season / Sex / Weaning Management / Pasture / Weaning Group / Weaning Date

Calves born in a single breeder’s herd, in the same year, in the same season, of the same sex, and managed the same are included in a birth contemporary group. Those same calves that were raised in the same weaning management group, in the same pasture, and weighed and weaned on the same day are included in the weaning contemporary group.

Best Practices:

Reporting or registering only the “best” animals in a contemporary group is inappropriate and counterproductive. All comparisons are made within a contemporary group, so by leaving out the bottom end you are making your “best” animals appear to have less comparative performance. This results in inaccurate EPD.

Report true managemental differences so that unintended bias is not introduced. If you report an entire calf crop as a single contemporary group, but some calves were developed on pasture with supplement and some weren’t, it is vital to account for those managemental and nutritional differences in order to predict the genetic differences.

Docility

Docility records help evaluate the disposition of an animal, and in a genetic evaluation help determine the genetic merit of individuals’ progeny for improved temperament. Assess docility at either weaning or yearling. Score an entire age group of cattle at the same time (don’t score some at weaning and others at yearling). The following table describes the chute scoring method used by the ASA. Have one person do all the scoring (avoid one person doing some of the cattle and another person scoring the other portion). Being consistent is key to subjective measurements like docility.

1 = Docile. Mild disposition. Gentle and easily handled. Stands and moves slowly during processing. Undisturbed, settled, somewhat dull. Does not pull on the headgate when in a chute. Exits the chute calmly.

2 = Restless. Quieter than average, but may be stubborn during processing. May try to back out of the chute or pull back on the headgate. Some flicking of tail. Exits chute promptly.

3 = Nervous. Typical temperament. Is manageable, but nervous and impatient. A moderate amount of struggling, movement, and tail flicking. Repeated pushing and pulling on the headgate. Exits chute briskly.

4 = Flighty (Wild). Jumpy and out of control; quivers and struggles violently. May bellow and froth at the mouth. Continuous tail flicking. Defecates and urinates during processing. Frantically runs the fence line and may jump when penned individually. Exhibits long flight distance and exits the chute wildly.

5 = Aggressive. May be similar to score 4, but with added aggressive behavior, fearfulness, extreme agitation, and continuous movement, which may include jumping and bellowing while in a chute. Exits the chute frantically and may exhibit attack behavior when handled alone.

6 = Very Aggressive. Extremely aggressive temperament. Thrashes about or attacks wildly when confined in small, tight places. Pronounced attack behavior.

Growth Traits

Collecting individual calf and weight measurements from birth until yearling is an important practice to measure performance for a wide range of traits. These traits serve as the foundation for most genetic evaluations.

Birth weight records should be collected on calves within 24 hours after birth. Hoof tapes are an acceptable method to measure birth weight, but please indicate when a tape is used, and use the same method for the entire calving season.

Weaning weight data should be collected from 160 to 250 days of age. It is important to remember that weaning weights will be adjusted to a standard age. While taking weaning weight measurements, it is recommended that producers also capture docility scores.

Docility can be measured using the 1–6 grading scale, where 1 is an extremely gentle animal and 6 is extremely aggressive.

Feet and Legs

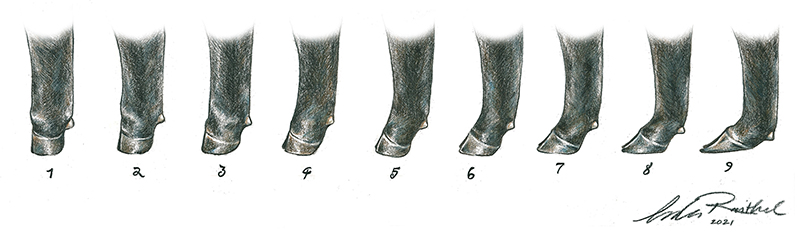

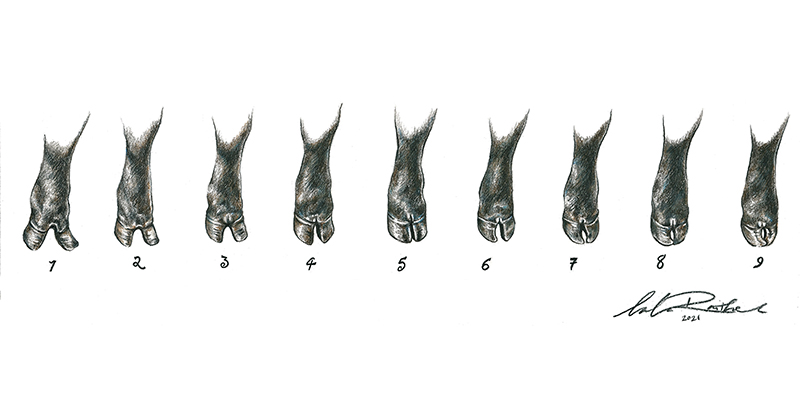

Proper feet and legs conformation leads to improved soundness and lower incidence of culling. Members are encouraged to evaluate all yearling animals annually and mature females every couple of years for feet and legs conformation issues. A 1–9 rubric is available to score animals for three traits: Claw Shape, Hoof Angle, and Rear Leg Side View. These traits are important to overall soundness and those phenotypes can be used in a genetic evaluation. The ASA is currently accepting phenotypes from membership for a future research EPD development project.

Hoof Angle describes the angularity that exists between the base of the hoof to the pastern. Can describe steepness, shallowness, and length of toe.

Claw Shape describes digital conformation with regard to shape, size, and symmetry. Can describe divergence and openness, or curling/crossing of claws.

Feed Intake

Individual feed intake records are an important component in evaluating an animal’s genetic merit for feed conversion. These records are often taken post-weaning or around yearling age. Growth is also measured during the intake test period.

Warm-up period:

Depends on the background of the cattle and the type of feed intake system. If calves are already accustomed to eating out of bunks, a seven-day warm-up period with the feed intake system is likely adequate. For cattle that have not yet been bunk-broke, they could need up to a 21-day warm-up period.

Feed Intake Test:

Recommend a 42-day minimum, which allows for missed days due to weighing or problems with the intake measurement. Records should be submitted as a measure of dry matter intake.

Weights:

Animals should be weighed two days in a row (to adjust for fill) at the start of the test and at the end of the test. Or cattle can be weighed five times throughout the test period.

Mature Cow

Mature female data is useful for determining female productivity and maintenance requirements.

Mature cow weight records can be collected at any age after yearling. Entire cow groups should be weighed on the same day and within 45 days of weaning their calf. If weighing the entire cow herd is not feasible, weigh age groups (for instance, all two-year-olds and six-year-olds). Members can submit weights for cows of any age between two and 12. Records on the same cow across multiple years are accepted.

Body condition scores (BCS) are recommended to be taken at the same time as mature weight collection. Entire cow groups should be scored on the same day, and by the same person, for contemporary grouping. The ideal score should be 5 to 6.

Performance Data Collection Guide

When it comes to performance data collection, the seedstock breeders, cow-calf operators, managers, and hired hands all play a pivotal role in collecting phenotypic measurements and reporting them into a system to use the information to its fullest extent. This rests on your shoulders. If you want to get the most complete picture of the genetics of your herd, then you have to commit yourself to collecting the most complete set of records AND using them to analyze your operation and your genetics.

It is not enough to measure the animals and write it down in your record book or in a notebook. Records sitting in a pile of papers on your desk will NOT be used to their fullest extent. I empathize that feeding records into an analysis of your herd’s performance or a genetic evaluation is not an easy task, nor do many of us wish

to spend hours with a computer working on this step. But in order to use your herd performance to its fullest, this is a necessary step. This might mean you hire someone to help digitize your records, twist the arm of a family member, or simply sit down and do it yourself. There are many approaches and software platforms to use. My advice is to find a system that works for you so that you USE the records you collect.

The following information is to clarify the best approach for collecting various performance records and to provide a one-stop shop with the information you need to gather these data points. This article breaks down each type of phenotypic record and the best way and time ranges to collect them to take away any indecision surrounding this essential component of beef cattle improvement.

Pulmonary Arterial Pressure

High-altitude disease, commonly known as brisket disease due to the swelling around the neck and brisket of the animal, is a disease affecting cattle resulting in decreased heart function. This typically results in approximately 3–5% of all calf death loss for herds managed in higher elevations, which is worsened (~20%) when bringing low-elevation-adapted cattle up to higher elevations.

Pressure measured in the pulmonary artery (PAP) is used to confirm the presence of hypertension and can be an effective gauge of the pressure put on the heart to transport oxygen throughout the body. In higher elevations, where there is less atmospheric oxygen, PAP issues can result in decreased performance, poorer fertility rates, and in many cases, death. An indicator for high-altitude disease resistance is a low-PAP phenotype.

Breeders in high-elevation regions of the country are encouraged to consider collecting a PAP phenotype on their animals for two reasons: 1) a PAP phenotype can be an effective indicator of an animal’s ability to survive in high elevation, and 2) a PAP phenotype can be useful in a genetic evaluation of PAP to determine an animal’s ability as a parent to pass favorable genetics to progeny.

The ASA has a PAP EPD predicted through International Genetics Solutions for animals within five generations of an animal with a PAP phenotype. The PAP EPD can be located in the EPD suite on individual animal pages on Herdbook.

To report data, please send a spreadsheet to simmental@simmgene.com with the following information:

- Animal ID

- ASA Registration Number

- Date of Collection

- Technician

- Elevation

- PAP

Ratios

Animal performance within a contemporary group can be expressed as a deviation from the contemporary group mean. A trait ratio can be an effective way to rank animals within a group and can be used as a low-accuracy substitute to make selection decisions when EPD are not available. Trait ratios are calculated by:

Trait Ratio = (Adjusted Trait Group Mean Trait ) X 100

Animals with reported measurements outside of normal limits or beyond accepted age ranges will not receive ratios. Animals in a single animal contemporary group will receive a ratio of 100.

Stayability

Stayability is perhaps the most economically relevant trait to beef cattle production as it represents the ability of cows who have a calf at two years old to remain productive in the herd until she has paid for her developmental costs. Research has suggested that the average age at which a commercial female has paid for her developmental costs, given she had a calf every year, is six years of age. The stayability evaluation uses a random regression model to predict the difference in probability that a cow will have a calf every year until she has had her fifth calf. Only females that first calve at two years of age will enter a stayability evaluation. This is meant to exclude those yearling animals that are sold commercially, where data reporting is unlikely.

This evaluation highlights the importance of the Total Herd Enrollment (THE) program, which captures annual cow productivity data.

How stayability data is collected:

Dam calved at age 2 - necessary to be included in the Stayability evaluation.

Dam calved at age 3

Dam calved at age 4

Dam calved at age 5

Dam calved at age 6